Remembering Paul Williams

By Doug Meigs

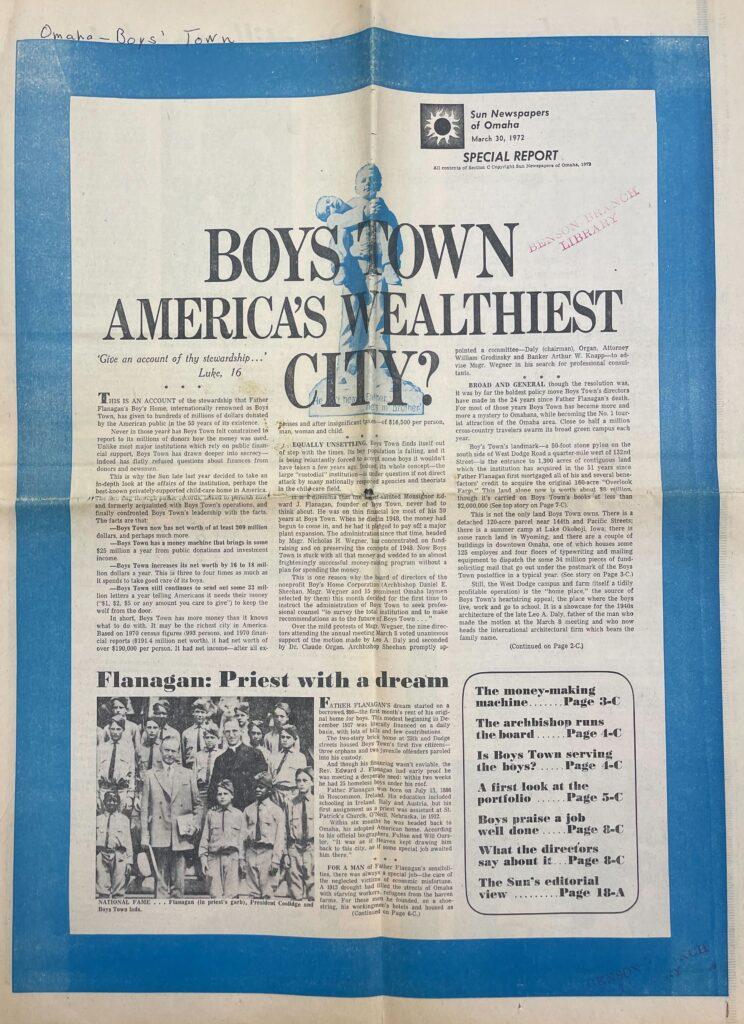

In towering all-caps, a 1972 Omaha Sun headline proclaimed: “BOYS TOWN: AMERICA’S WEALTHIEST CITY?” followed by a biblical quote: “‘Give an account of thy stewardship…’ (Luke, 16)”

So began an eight-page broadsheet investigation into the murky finances of Boys Town, an esteemed charitable institution that Father Edward J. Flanagan (now on the path to sainthood) established in 1917 to serve homeless, neglected and underprivileged boys.

When the Sun published its special report, 55 years had passed since Father Flanagan founded his orphanage on a $90 loan. He built Boys Town from a downtown boarding house into a 160-acre village with its own zip code on the rural outskirts of Omaha, Nebraska. It was a national icon of unassailable charitable good. Or so it seemed. A new priest was in charge, and Boys Town employed a robust marketing effort mailing 33 million letters a year begging for donations “to keep the wolf from the door” (while reaping $25 million annually from public donations and investment income, according to the Sun’s reporting).

After Boys Town refused to answer local journalists’ questions about finances, the Sun began digging into federal 990 tax forms to expose how — despite a staggering asset portfolio — the institution was serving fewer youths (only 750 in 1972) with a net worth of $209 million and growing. By the end of 1971, the “Boys Town population had dropped and its endowment had risen to about $215,000 per boy” (adjusted for inflation, that’s $1.7 million per youth in 2025 dollars). The Sun reported that the nonprofit was richer than any Nebraska company and ranked about 230th in Fortune magazine’s 1970 list of top-500 industrials.

Public outcry and institutional reform followed the investigation. As a result, Boys Town diversified its mission and community service model, eventually expanding into hospitals, scientific research and revamped residential programing. And the Omaha Sun won the 1973 Pulitzer Prize for Local Investigative Specialized Reporting. It was the first time a weekly had won the prestigious honor. The only other Pulitzer wins for the city had gone to the much larger daily — the Omaha World-Herald — for editorial writing (1920), public service (1943) and photography (1944).

The editor responsible for the Sun’s investigation was Paul Williams. The Pulitzer win established his journalism renown and preceded his career path into academia — and his place in establishing a new nonprofit: Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE).

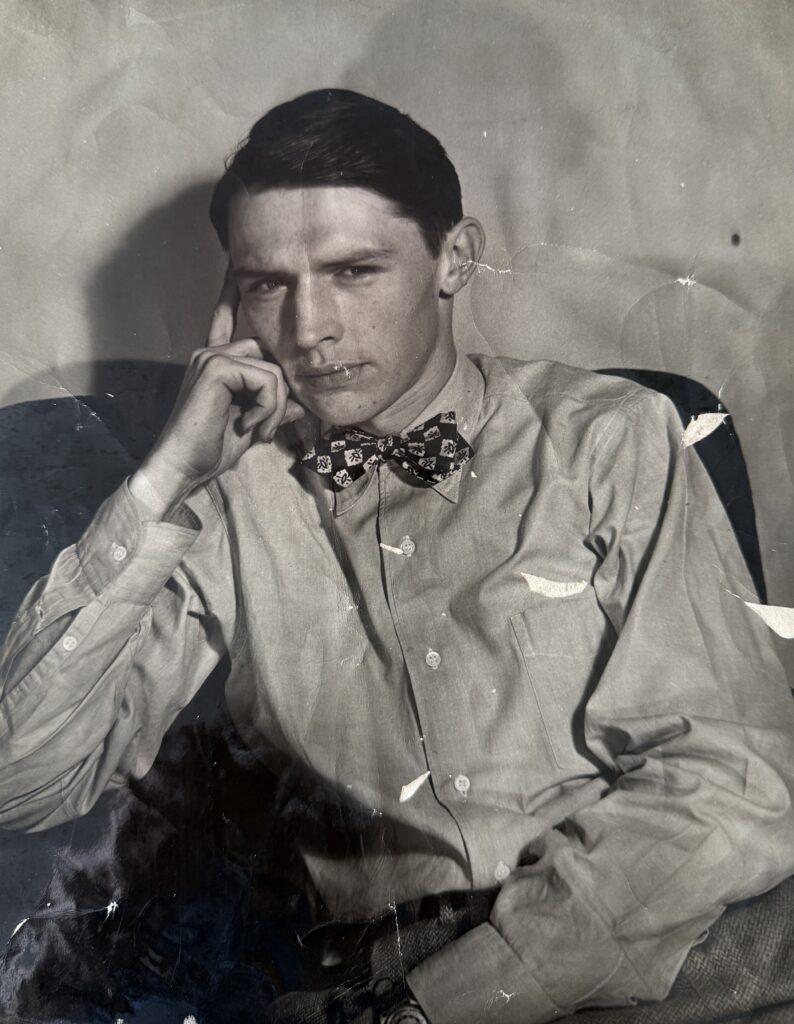

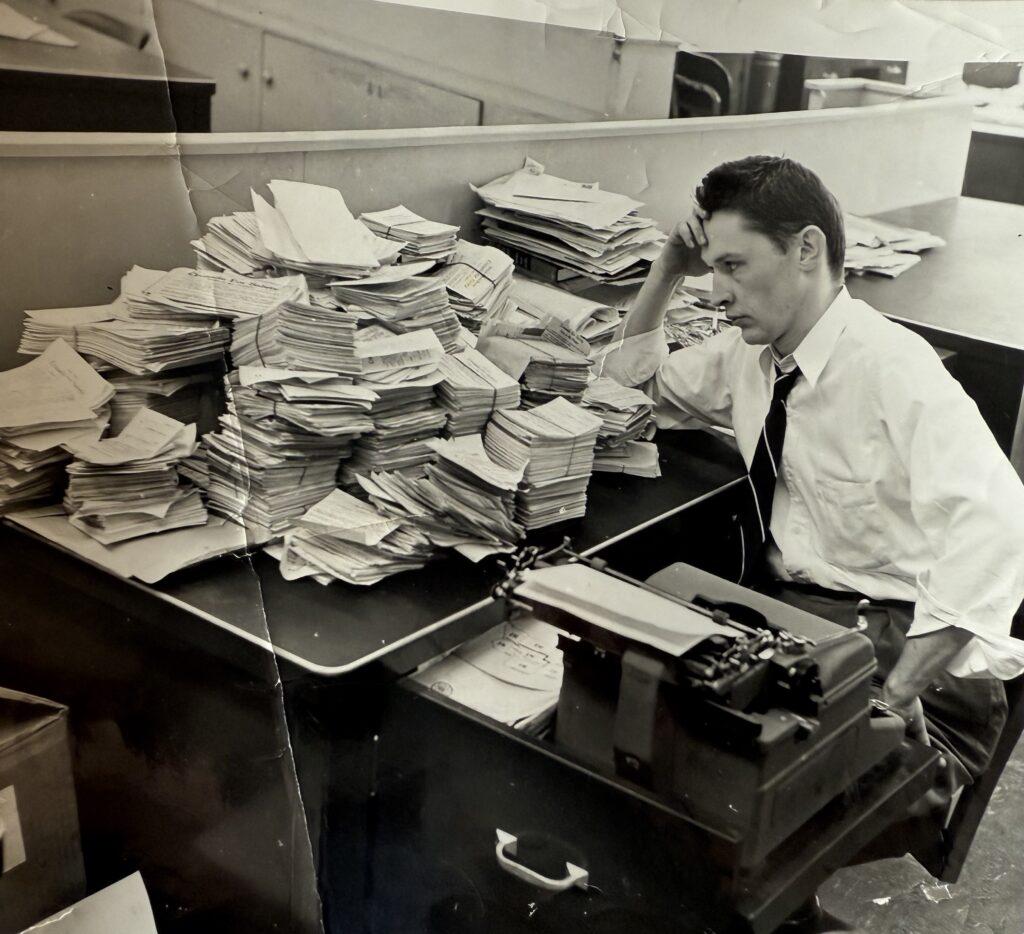

Williams was born in Topeka, Kansas, in 1922. The Topeka High Historical Society boasts how the 1939 grad demonstrated early literary talent as a spelling bee champ. His obituary in Ohio State’s daily student-run newspaper, The Lantern, notes that Williams “began his newspaper career in 1941 as a copy editor and reporter for the Stauffer newspapers” (which owned the Topeka State Journal and Topeka Daily Capital).

The “Paul N. Williams Papers,” archived at the State Historical Society of Missouri, offer a wealth of information about his life and legacy. He attended the University of Kansas, Washburn College and the University of Nebraska, and he flew 40 combat missions in Europe as a navigator on a World War II U.S. Air Force bomber. In 1946, he began reporting at the Omaha World-Herald and worked his way up to assistant city editor. After also working as a correspondent for Time and Newsweek, he joined the Omaha Sun from 1960 to 1973. He was the top editor for the local chain of newsweeklies serving the Omaha metro area.

While Williams was busy editing the Sun, a financial star was rising in Omaha. Investor Warren Buffett was steadily buying more shares in a company called Berkshire Hathaway. That same investor eventually purchased the Sun in 1968. The Sun was the first of many news industry acquisitions for Berkshire Hathaway and the man known as “the Oracle of Omaha” (who became the richest man in the world for a brief period). Buffett would also eventually buy the then-defunct Sun’s rival — the Omaha World-Herald — and roughly 30 other daily newspapers before divesting from print with the sale of BH Media Group to Lee Enterprises in 2010.

Doug Smith was part of the Sun’s Pulitzer-winning team, and he has vivid recollections of his former boss. He first met Williams while caddying at a local golf course. A few years later, as a fresh graduate from Northwestern University, Smith wrote a funny letter to the Sun’s editor, and Williams called to offer the 23-year-old a job — his first full-time employment. (Although he worked at the Sun and later the World-Herald, Smith is better known in Omaha for his career after journalism, having established the Omaha ad agency Ervin & Smith.)

“I had no experience, really,” Smith said. But after 18 months of slogging through general assignment work, he got a promotion to what they called “The Four Way staff,” the Sun’s regional investigative team. Soon after, the newspaper’s owner and editor organized a clandestine meeting at the upscale Blackstone Hotel to discuss strategy. Coincidentally, the Boys Town board of directors was holding their annual meeting just one room away.

“I was put in charge of this long-term, low-level investigation,” Smith said. “What did they own? How did they operate? What was their history, etc., etc. And I worked a lot with the Boys Town PR guy — and I don’t know if investigative guys feel bad about it, but I felt bad after because … I didn’t mislead him, but I didn’t tell him what we were up to.”

At one point, Smith discovered there was a Boys Town marketing service center of sorts near the courthouse. He said it was “full of ladies typing letters to donors.” With 60-some typewriters click-clacking all at once, Smith and photographer Len Cook “just burst in and started taking photos. And this guy is like, ‘Please! Please! We don’t want people to know about this.’ Of course, that was a great quote, and it just kind of showed how there was sort of a deception going on.”

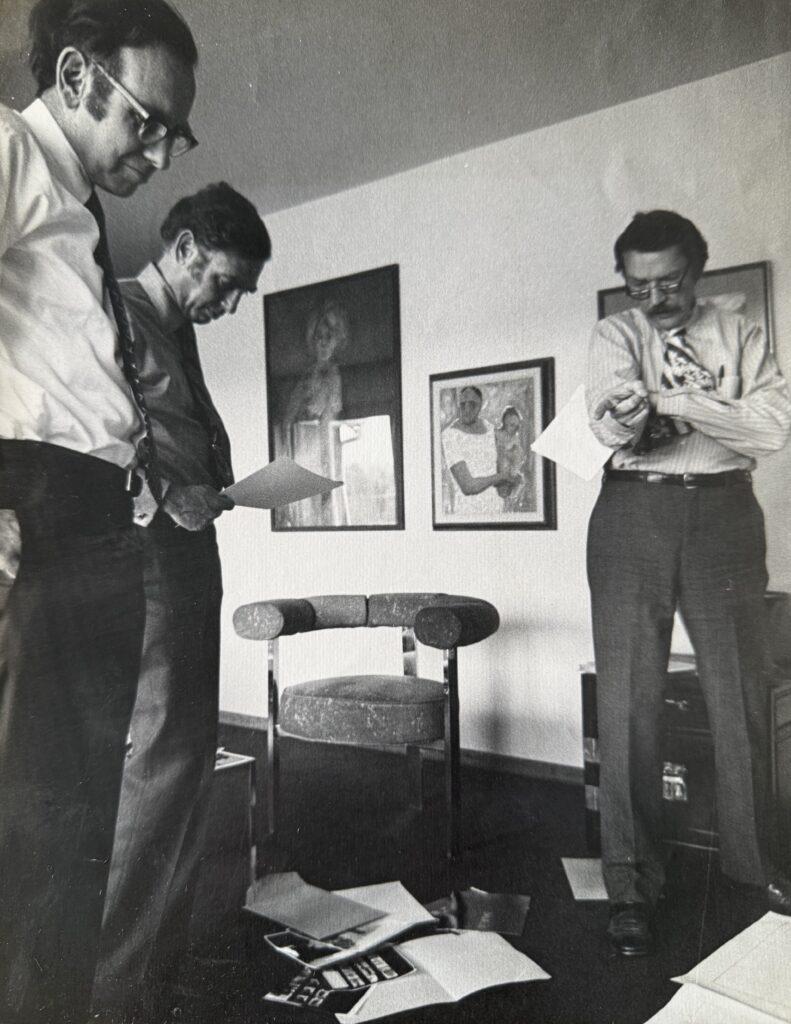

Smith’s own contributions to the investigation came on top of his routine daily assignments. Toward the end of the Boys Town project, as the pieces came together, they set up a control room in Williams’ home — “to keep it secret.” Smith said they were terrified that the World-Herald would scoop their lead from the 990 IRS forms and assign a dozen or more reporters to coverage. It was during one such meeting at William’s home when Smith experienced his proudest moment as a journalist. Smith and other members of the team (which also included Mick Rood, Wes Iverson and Randy Brown) were polishing their stories in the basement, filing upstairs to Buffett and Williams. “They were reviewing copy as it came up, and Buffett’s voice came down the stairs, ‘This is an excellent piece, young man.’ And I was so proud.”

That investigation was the only time when Smith could remember Buffett being involved in editorial production. He was otherwise hands-off from the news. “I really want to emphasize this,” Smith added. “The investigation was handed to us on a platter by Warren Buffet.” The financial guru helped them secure the 990 tax form, which Smith said was more difficult to obtain in those days. Buffett even contributed investment analysis to the reporting team — although his byline was not included. Several articles probed the nonprofit’s assets, listing its complete stock market portfolio. “Boys Town was so rich, and he showed that their return was about half what it should have been, and their risk was about twice what it should have been,” Smith said.

Williams left the Sun and took a job as assistant professor at Ohio State’s journalism program the same year they won the Pulitzer. The newly minted faculty served as advisor to the school’s student-run daily, The Lantern. Under his leadership, the publication was named the nation’s “best all-around student newspaper” in 1975 by the Society of Professional Journalists’ Sigma Delta Chi Awards. He also began writing a book that featured interviews with 99 of the day’s most influential investigative reporters and editors. The book, titled “Investigative Reporting and Editing,” was published posthumously after his unexpected death at age 54. Media scholar James Aucoin described the book as one of the earliest attempts to document a methodology for the field of investigative journalism.

His granddaughter Kari Hulac grew up to be a journalist, following in his footsteps. Hulac is editor-in-chief of Richmondside, a nonprofit newsroom serving the community of Richmond, California. She recently inherited his Pulitzer Prize certificate from her mother, Williams’ eldest daughter Patricia. “I think of him often, always recalling a story in his obit of him being a kind editor, who once told a cub reporter who wrote an unusable story that at least he spelled all the names correctly,” Hulac said.

Williams joined the Ohio faculty at a precarious time for American journalism. The Pentagon Papers (1971) and Watergate scandal (1972) had rocked the general public’s faith in government. Media outlets scrambled to feed audiences hungry for accountability reporting. Newspapers developed new investigative jobs for a growing cohort of muckrakers.

Some veteran journalists worried that a rush to produce shocking exposé could endanger the long-term viability of the emerging investigative reporting profession. It was with this in mind that Williams joined a group of journalists and supporters to establish the world’s first organization dedicated to training investigative reporters and editors in 1975. The organization’s name — inspired by a synonym for “outrage” pulled from a thesaurus — was Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE for short), and it is turning 50 years old in 2025.

Financial struggles plagued the early years of the fledgling nonprofit. Aside from basic general operating expense concerns, a crisis confronted the early membership. Arizona investigative journalist Don Bolles (who was going to speak at the inaugural IRE Conference) was killed in a 1976 car bombing. Bolles’ assassination galvanized IRE members to continue his work, and Williams was an early contributor to the project. The collaborative effort, known as the Arizona Project, spanned newsrooms across America and exposed IRE to legal liability from defamation suits.

James Aucoin’s book, “The Evolution of American Investigative Journalism,” notes that the Omaha World-Herald was among one of the early independent newspapers to donate in support of IRE. The Omaha Sun’s owner also made a donation. Aucoin wrote that “Warren Buffett donated stocks to IRE that were sold, providing a cash donation of $787.”

Williams arranged for IRE to be based out of Ohio State University’s journalism school. But his untimely death (from a heart attack following a bout of pneumonia) disrupted those plans. Ohio State was out, and IRE needed a new home. Eventually, the country’s oldest journalism school came to the rescue. IRE has operated out of the Missouri School of Journalism ever since.

Today, IRE’s membership of nearly 5,000 journalists make it the world’s largest member-based journalist organization. Half a century after Williams and friends established IRE, the organization remains focused on educating and advancing the future of investigative journalism.

Looking ahead to the next 50 years of investigative journalism, IRE’s current fundraising efforts bring to mind a cautionary quote attributed to the Oracle of Omaha: “Do not save what is left after spending; instead spend what is left after saving.” Had IRE’s early board of directors managed to hold onto Buffett’s stock donation, the organization today would have found a considerable nest egg. A single A-share of Berkshire Hathaway is now valued at nearly $700,000.

If Buffett were to make a donation of shares to IRE in honor of its 50th anniversary — maybe matching what he donated at the onset of IRE’s establishment (in memory of Paul Williams, perhaps) — it would be the single largest donation in the organization’s history.