Capturing global investigative journalism’s oral history

By Silas Tsang, WTOL-TV

There is a new effort to document the oral history of investigative journalism around the world. It’s the brainchild of investigative reporter Adiel Kaplan at Columbia Journalism School. The goal of her project is to preserve key perspectives on how the methods and tools of accountability reporting spread globally since the 1970s.

The timing of her research is pressing. Many of the journalists key to that spread are entering retirement age. A few have passed away. Kaplan, who teaches for Columbia’s investigative journalism program, teamed up with oral historians from the university’s Incite Institute to gather and archive their personal stories and professional accomplishments. Over the next three to five years of interviewing and archiving, they plan to build a concrete blueprint for future generations to pursue investigative journalism across jurisdictions and governments worldwide.

“We’re looking at the last 50 years of investigative reporting around the world and the people who built networks, shared skills and tools and ran collaborations across countries and regions,” Kaplan said. “Many of the central people to that work are retiring and getting older, and in many places, their work and legacies are under increasing threat. Preserving their stories, methods and accomplishments so that current and future generations can learn from them is more important than ever.”

Kaplan has begun interviewing journalists for the project. Interview subjects include Brant Houston, the Knight Foundation Chair in Investigative and Enterprise Reporting at the University of Illinois. Houston was a former IRE executive director who spent 17 years in newsrooms prior to academia. His interview at the NICAR25 Conference focused on his role in establishing the National Institute for Computer-Assisted Reporting under IRE, co-founding the world’s first global investigative journalism conference that grew into the Global Investigative Journalism Network, and co-founding the Institute for Nonprofit News.

Reflecting on his own career, Houston said his interest in journalism started during the Watergate scandal in 1972 when he was a paperboy for The Boston Globe. “I read the stories closely. I spent a summer watching the Watergate hearings. I was fascinated,” he said.

Houston said the intense public outcry for accountability is what inspired him to make a career out of seeking accountability. Recalling his first investigation as a journalist, he explained how he was following the story of a Black woman who resigned as a teacher from a local school because students were taunting her with racial slurs. He visited the woman’s home, but she wasn’t there. If the young reporter wanted to speak to her, he would have to get past her husband.

“We’ll have a glass of bourbon, and she’ll call in. I’ll decide whether or not she should talk to you,” the man told him. “And she called in and he said, I think this kid’s OK, you can talk to him, and she confirmed the whole story. And all sorts of things blew up. The Department of Justice came in to do an investigation.”

Although investigative journalism existed in America in various forms at least since the muckracking days of the penny press, a more established form of investigative reporting began to spread after the Watergate scandal. Newsrooms created investigative units. IRE formed in 1975 to help investigative journalists share values and best practices for the craft, and other nonprofits emerged to advocate for investigative reporting in America and abroad. The models pioneered in the U.S. spread worldwide. Since its founding in 2003, the Global Investigative Journalism Network’s membership has jumped from 35 to 263 nonprofits in 97 countries.

Sheila Coronel co-founded the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism in 1989, one of the earliest such groups worldwide (established the same year as the Center for Public Integrity). Kaplan said Coronel’s center was likely the first nonprofit investigative newsroom outside of the United States. Before the Philippine center, Mother Jones started as a nonprofit investigative magazine in 1976, and The Center for Investigative Reporting began in 1977 (both U.S. outlets based in the San Francisco Bay Area. Mother Jones published some of CIR’s earliest big investigations, and the two merged into one organization last year.

Now the director of the Toni Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at Columbia Journalism School, Coronel explained the place for her nonprofit within the context of 1980s Philippines.

“Democracy had been restored only in 1986, and it was a very fragile democracy,” she said. “Investigative reporting thrives best in places where there’s a free press and rule of law.”

She said the political upheaval in Asia created an opening for investigative reporters to expose corruption and to hold the powerful accountable. It may seem different from Houston’s story. But these — and many of the oral histories Kaplan has gathered so far — demonstrate a shared thirst for holding truth to power and advocating for the common man.

Coronel recalls one of her first investigations, which exposed corruption in the Philippines.

“There was this very controversial case that involved the telephone company that had a monopoly of telecommunications in the Philippines.” she said. “Our investigation showed that the Supreme Court decision that basically preserved the monopoly against a competitor was not written by the Supreme Court justice whose name was on the decision, but by the lawyer of the telecommunications monopoly.”

According to Kaplan, one of the more interesting challenges she faced in beginning to work on oral history was adjusting her interview style. She’s a second-generation investigative reporter and she’s worked in newsrooms. The questions an oral historian might ask an interviewee are different from what a beat reporter might ask law enforcement at the scene of a crime. Less about a good quote and more about being a facilitator.

“The interviewer isn’t after a specific answer, but is more of a facilitator, helping the interviewee tell their personal history within the context of the project focus — in this case, the global spread of investigative reporting,” she said. “The stories we’ve already gathered have been fascinating and informative, really underscoring why capturing this history is so important.”

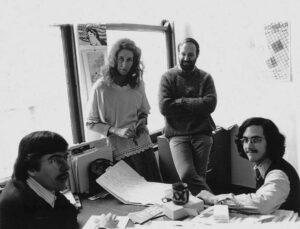

Kaplan’s ties to this project run deep. Her father, David E. Kaplan (who retired in 2023), was the first executive director of the Global Investigative Journalism Network, working alongside Houston there for more than a decade, and a longtime IRE member who has received numerous honors from the organization. Many of the initial interviews she’s done have been with longtime IRE community members, including Brant Houston, Sheila Coronel, and Center for Investigative Reporting founders Dan Noyes, David Weir and Lowell Bergman. Coronel was IRE’s keynote speaker in 2016.

Momentum for the oral history project is growing. Kaplan received seed grant funding earlier this year, allowing her to travel and conduct more time sensitive interviews. The project is housed at the Columbia Center for Oral History Research within Incite Institute, which has led other multi-year oral history projects, including the Obama Presidency Oral History. In the current, early phase of the project, Kaplan is focused on collecting firsthand accounts from journalists who helped shape the global rise of investigative reporting between 1975 and 1990 — stories that reflect how the craft took root across different regions, political systems and eras.

The final product will be a public-facing digital archive, which the team hopes to make available in as many languages as funding allows. Kaplan and the Incite researchers expect it will lead to publication of numerous resources, including academic research, journalistic articles and teaching tools.

Visit Columbia University’s Incite Institute to learn more about the Global Investigative Journalism Oral History Project